|

|

Chamaeleo

(Chamaeleo) calyptratus

|

| Scientific name |

Common

name(s) |

alternate scientific names |

described by |

year |

size |

brood |

|

Chamaeleo (Chamaeleo) calyptratus

|

Veiled or Yemen Chameleon |

Chamaeleon calyptratus

see a species list of Chamaeleo |

Dumeril & Bibron |

1851 |

Large |

Eggs |

This is a large, aggressive species and one of the most widely recommended for the novice. Males may reach a total length of 17-24 inches (females 10-13") with a SVL of 8-12" (females 4-6"). Males may weigh from 100-200 grams and females 90-120 (considerably more when gravid). It is generally suggested that beginners purchase a male to avoid potential problems with dystocia (egg-binding) that are often seen in females who have not been given a proper laying site and/or have been overfed.

Indigenous to the southwestern coastal regions of Saudi Arabia and western Yemen, the veiled chameleon occupies the wadis and agricultural lands of this otherwise arid region. The nominate form, C. calyptratus calyptratus is found in the more southern reaches of the distribution (Yemen and southwestern Saudi Arabia) while C. calyptratus calcarifer is found in the more northern part of the species' range (western Saudi Arabia). Recent reports also indicate one or more feral populations of C. c. calyptratus on Oahu (G. Homatas, personal communication) and Maui (http://www.state.hi.us/dlnr/chair/pio/HtmlNR/02-23.htm). Unlike the feral populations of C. jacksonii in Hawaii, C. calyptratus is large enough to consume fledgling birds, making them the greater ecological threat to the native fauna.

The hallmark of this species is its impressively high casque that may exceed 3"-4" in the nominate form, C. c. calyptratus when measured from the rear corner of the mouth. The casque of C. c. calcarifer is only a little over 2". Adult males have a higher casque than females and tend to be significantly larger. Some authorities have suggested that the casque may serve as a device to aid the collection of water while others believe that it might serve in heat dissipation. A more recent (unpublished) speculation is that the casque might serve to amplify the low frequency "buzzing" used by veileds to communicate. Similar crests are thought to have performed that function in some prehistoric sauropods. This infrasonic communication was first described by Kenny Barnett and his colleagues in an article published in the journal, Copeia. (Barnett, K. E.; Cocroft, R. B.; Fleishman, L. J. Possible Communication by Substrate Vibration in a Chameleon. Copeia; 1999(1):225-228. 1999). See http://www.geocities.com/RainForest/Vines/5014/hoot.html for more information on this phenomenon. Subsequently, there have reports of similar behavior in numerous chamaeleonid species. Below is a partial list of species reported in personal communications to exhibiting the "buzzing" behavior similar to that of C. calyptratus.

- B. decaryi (E. Edwards)

- B. thieli (E. Edwards; L. Horgan)

- C. dilepis (K. Barnett)

- C. Johnstoni (F. LeBerre)

- C. melleri (A. Banks)

- C. Oweni (F. LeBerre)

- C. senegalensis (K. Barnett)

- F. ousteleti (multiple ADCHAM list members)

- F. pardalis (multiple ADCHAM list members)

- R. brachyurus (J. Mease)

- R. brevicaudatus (J. Mease)

- R. kerstenii robecchii (E. Edwards; J. Mease)

- R. uluguruensis (J. Mease)

The most unambiguous way to sex this species, however, is to look for a small "tarsal spur" on the back of the rear "ankle." (The tarsal spur is pictured in the Illustrated Glossary). These are apparent at birth in males and are lacking in females. There are prominent gular, ventral, and dorsal crest made of enlarged, conical scales. Broad vertical bands of various shades of green, yellow and brown adorn the sides. Females in gravid coloration exhibit a darker, brownish background, often dotted with striking purplish-blue spots.

Because veiled chameleons come from Saudia Arabia and Yemen it is sometimes assumed that their hydration requirements are less demanding than those of most other chameleons. The fact is, however, that these animals are most abundant in mountainous coastal regions where rainfall can be heavy and even in the absence of rain, fog conditions create significant condensation. The animals drink the dew off of leaves and other wet surfaces. Veiled chameleons require the same regimen of misting and drip systems as do most other chameleons. Because of their large size, a screen cage of at least 24"x24"x36" is recommended but 24"x24"x48" is much preferable.

Veiled chameleons are often voracious feeders and readily accept accept all of the common feeder insects. But unlike most chameleons, veileds will often include vegetation in their diets. Such foods as iceberg lettuce and other nutrient poor items should avoided but a wide variety of foods may be offered. These include blueberries, thin slices of apple or pear, diced zucchini, butternut squash, red pepper, dandelion leaves, collard greens, kale, and other vegetables that are often used to gut load prey items. A list of these items may be found in the James/Wells/López gut load recipe found in the "Insects" section of www.adcham.com. Some veileds will all but defoliate cage plants such as pothos while others cannot be coaxed to accept any vegetable matter in their diets.

Reproduction is oviparous. Thirty - sixty eggs are laid per clutch although on rare occasions over 80 eggs are laid. Because these larger numbers of eggs are decidedly unnatural and because of the extreme stress that such a clutch puts on females, it is recommended that all females approaching breeding age (6 months) be placed on a restricted feeding schedule. This reduces the clutch size (whether or or not the females are bred) and dramatically increase the life span of the female. As indicated in the previous sentence, females can lay infertile eggs if not bred, and should, therefore, always have some place within the cage to lay them in. A plastic container such as a pet-pal (without the lid) that is big enough for her to fit into about half full of washed sandbox sand can be placed in her cage. Using a container this size gives her a place to start digging but doesn't take up a lot of space in her cage.

Once she has started to dig, she can then be moved to a larger container where she can lay her eggs. A 65 liter Rubbermaid-type storage container with a modified lid works well. (Lid modification = cut a hole in the lid and cover the hole with screen). A whole bag of washed sandbox sand may be placed in the container in a pile at one end and moistened so that it will hold a tunnel (not collapse on her when she digs). A branch should be placed in the container. Put the female into the container and replace the modified lid. Add a light over the screen part of the lid to provide heat and light for her. She may dig a few test holes first. While she is in the container, the sides of the container should be misted to provide her with water and the sand should be kept moist. Care should be taken not to disturb the female while she is digging or laying. If she is in the container for a few days, she may be fed. No insects should be left in the container or they may nibble on the eggs or the female. Once she turns around with her behind in the hole to lay her eggs, the light may be left on until she finishes laying burying them. When she has finished burying the eggs, she may be removed from the container and placed back into her cage and the eggs may be dug up. A plastic spoon may be used to carefully dig up the eggs... scraping away one layer of sand at a time until the eggs are reached. The eggs should be removed carefully being careful not to turn/rotate the eggs when moving them. Eggs require 6-8 months of incubation with temperatures varying from 68ºF at night to a day time high of 85ºF.

Moist vermiculite seems to be the preferred medium although sand, soil and peat moss have all been used successfully. Leave enough room in the container above the vermiculite so that the hatchlings have room to move around when they hatch until they can be removed. Chronically high temperatures and/or excessive moisture in the medium reduces the hatching rate and viability of the offspring. Females retain sperm and may require only a single mating to lay two or more consecutive fertile clutches.

Although females are able to breed at about 6 months of age, until they are full grown, they are still growing their own bones, so the author feels that it would not in their best interest to put demands for egg production on them as well. When the time to mate her comes, the female may be shown to the male by holding her on a stick outside the male's cage so that they can both see each other. Watch the following reactions to decide if they are ready to mate. Sometimes the male will react with aggression at first until he realizes that it is a female...so by keeping the female outside of his cage but in his sight, gives him time to calm down while she is safe. If she is not receptive she will gape at him and sway back and forth from side to side possibly hissing and lunging at him as well. Her background coloration will darken. If she is non-receptive, it could cause him to show aggression towards her. All of these possibilities are good reasons for keeping them separated until you see that she is receptive and that he has calmed down. If she is unreceptive or he doesn't calm down, the procedure may be repeated in a few days. If she is receptive, she will remain passive/calm and will likely move slowly away from him waiting for him to follow. She may "hug" the branch too. If she is receptive, and he is calm then she may be placed into his cage...but continue to watch them to make sure that things are going well. Sometimes the male will head-butt the female before mounting her. The female may be left in the cage with the male until she starts to repel/reject him. Again, they should be checked off and on to make sure that things are still going well. The female will take on a coloration that will be almost black in the background with bright mustard and torquoise markings indicating that she is gravid by the time of removal. This dark background coloration doesn't usually remain when she is out of the male's sight but will recur if she sees the male again.

Contributed by L. Horgan and E. Pollak.

References

Barnett, K. E., Cocroft, R. B. and Fleishman, L. J. 1999. Possible Communication by Substrate Vibration in a Chameleon.

Copeia, 225-228.

Bartlett, R. D. and Bartlett, P. 1995.

Chameleons: A Complete Pet Owner's

Manual. Barron's Educations Series, Hauppuage, NY

Davison, Linda J. 1997. Chameleons: Their Care and Breeding. Hancock House Publishers, Blaine, WA.

De Vosjoli, P. and Ferguson, G. 1995.

Care and Breeding of Chameleons.

Advanced Vivarium Systems, Santee, CA.

Klaver, C. & W. Boehme. 1997. Chamaeleonidae.

Das Tierreich, 112: i-xiv' 1 - 85. Verlag Walter de Gruyter & Co., Berlin, New York.

Le Berre, F. 1994. The New Chameleon Handbook. Barron's Educational Series.

Martin, J., 1992. Masters of Disguise: A Natural History of

Chameleons. Facts On File, Inc., New York, NY.

Necas, P. 1999. Chameleons: Nature's Hidden

Jewels. Krieger Publishing Company, Malabar, FL.

Schmidt, W., Tamm, K. and Wallikewitz, E. 1994a.

Chameleons, Volume I:

Species. T.F.H. Publications, Neptune City, NJ.

Schmidt, W., Tamm, K. and Wallikewitz, 1994b.

Chameleons, Volume II: Care and Breeding. T.F.H. Publications, Neptune City, NJ.

|

|

|

|

|

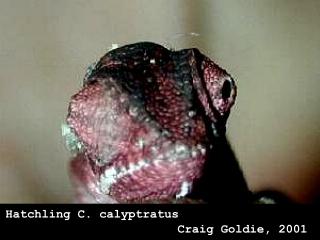

click on any thumbnail for a larger image

|

|

This page last modified on: Tuesday, September 24, 2002

|

© 2002-2005 ADCHAM.com

ADCHAM logo illustrated by Randy Douglas. Web site design by Look Design, Inc.

Do not reproduce or redistibute any of content of this web site without express written permission from the authors.

|

|

|